Indian Spirituality: Why is the West fond of it?

KAKALI DAS

Indian Spirituality

KAKALI DAS

Recently, on a widely watched American talk show, Trevor Noah welcomed the great Sadhguru with a fist bump.

That’s how mainstream Indian spirituality has become in the West.

The spread of ideas from the East to West has been going on since the time of the ancient Greeks.

But, it wasn’t until the 19th century that cultural practices from the Indian subcontinent began to get proper recognition in the West.

In the early 1800s, British scholars produced the first English translations of Indian sacred texts, after which American intellectuals like Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote about their fascination with these texts, in their essays and poems.

Other western teachers and spiritual seekers like Emma Curtis Hopkins and Helena Blavatsky relied on the concepts of Eastern religions to promote a new form of seeking God.

In 1893, at the World Parliament of Religions in Chicago, Americans were formally introduced to Eastern religions in their own homeland.

This gathering was attended by famous exponents of Hinduism, Jainism, Buddhism, Zen, Islam and other faiths, which were counted among emerging world religions at the time.

Indian Spirituality: Why is the West fond of it?

Among all of them, the address by one speaker in particular was declared a smash hit. Swami Vivekananda’s charisma and powerful oration captivated his audience – so much, in fact, that the crowd interrupted his speech with a long standing ovation. He went on to give many more lectures in the U.S. and U.K., and also established Vedanta Society in New York, which expanded to many American cities.

His confident knowledge of Hinduism, coupled with his perfect English, his noble demeanor and his pristine orange robes, made him the ideal ‘exotic’ mystic from the East and, also gained him attention from the ladies.

As other teachers visited the West after Vivekananda, some were greeted with hostility. And throughout the 1910s, the fear of women being seduced by ‘mysterious, dark-skinned pagans’ remained a prominent one. But by 1920, these sentiments began to change, when Paramahansa Yogananda came to America and established the Self-Realization Fellowship.

Gradually, he gained thousands of followers, and greatly influenced the Yoga movement in the West. In fact, Yogananda was the first prominent Indian to be hosted at the White House, and he was even dubbed the 20th century’s first superstar guru.

Clearly, Indian spirituality was gaining traction. But in the 1960s, one much loved boy band came and opened the floodgates. The Beatles’ trip to India to stay with their guru, Mahesh Yogi in 1968, put Indian spirituality in the limelight like never before. Although the group was wildly popular and their India visit received a lot of media attention, there were also other factors that influenced this rise in spirituality.

Mass communication and travel had become much easier. There was a widespread sense of unrest and frustration resulting from recent wars and people were experimenting with newer ways to feel fulfilled, for example, through psychedelic drugs. All this created the perfect environment that attracted young, idealistic individuals towards new philosophies picked up from the East.

Apart from disseminating teachings on simple living, yoga and meditation, these traditions offered spiritual counselling and methods of self-improvement.

‘I don’t want to have a nice job’ ‘I’d do anything, as long as I’m happy’ – the statements and philosophies as these began engrossing the minds of the youth during that time. For the more religiously inclined, the practices could offer a path to find God or salvation.

Because each individual’s path or goal could be personalised and distinct, experts believed that this aligned well with the American ethos of individual autonomy and freedom of choice. And so, Eastern ideas and practices went from being a niche counter-culture to a mainstream trend. The impact is everywhere – from medicine, psychology, and academia.

Words like ‘mantra’, ‘avatar’, ‘ashram’, ‘moksha’, ‘karma’ have become common parlance.

Today, while there are many gurus and ‘experts’ offering their advice, like Sadhguru or Deepak Chopra, the appeal remains the same – that of a happier, healthier life promised by a new form of spirituality. And the large-scale, wholehearted adoption of these practices has made spirituality India’s biggest cultural export.

While that may have benefited us economically and enabled better publicity – this has had a downside too – that we’ve ended up putting a price on spirituality and losing its complicated history and context along the way.

So that it can be neatly packaged and marketed globally, this form of spirituality gets sanitised in a way that removes it from its meaning and complex origins.

As a result, from Ayurvedic massages to Reiki, Buddhist singing bowls to palm reading, all things ‘exotic’ get lumped together because of convenience or ignorance. This leads to a diluted, sometimes incorrect understanding of different cultural practices. Let’s take Yoga, for example.

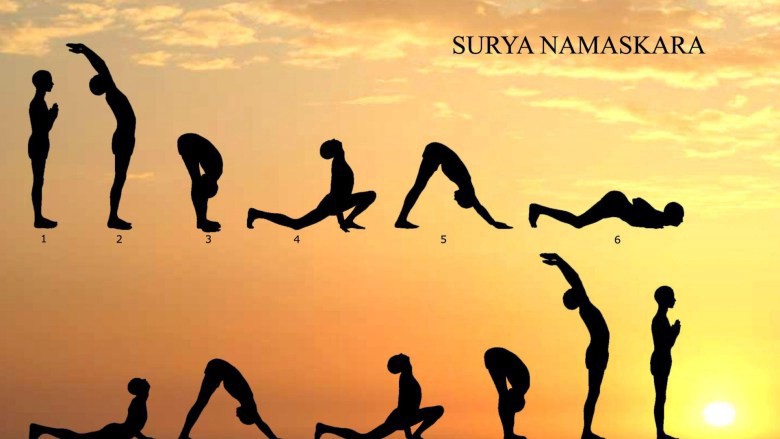

Scholars point out that even though Yoga has many complex histories in the Indian subcontinent, like Buddhist, Sufi, Jain, Tantra, popular Yogic practices like chanting Om and doing the Surya Namaskar (sun prayer) are actually tied to Brahminical Hinduism, in which the very use of Sanskrit has been forbidden to lower caste groups.

In the contemporary contexts, as Hindutva forces make special efforts to position Yoga as central to our national identity, yoga is becoming a tool to saffronise India, to define India as essentially Hindu, and define Hinduism as inherently superior. And yet, the Western Yoga industry continues to profit from Yoga as if it were a completely secular practice, even appropriating it at times.

A simple Google image search for fancy variations like Hot Yoga and Aerial Yoga will mostly show Western photos, and nearly nothing from India.

And unfortunately, because we still look up to the West in some ways, how the West interacts with spirituality impacts how we interact with it. For instance, experts say that it was the adoption of Yoga in the West, that cleared the path for India’s modern Yoga wellness trend, which made Yoga an attractive ‘upmarket’ English language based activity.

When we celebrate Sadhguru’s appearance on The Daily Show, the same West worshiping attitude becomes apparent because having any Indian on such a popular American platform seems like a big deal.

But actually, as many viewers pointed out, inviting Sadhguru to this show ends up giving credibility to this very powerful, yet very problematic man, who has been accused of promoting Hindutva sentiments through his philosophical teachings and whose sprawling ashram was allegedly built illegally on Adivasi land.

If we look at the growth of spirituality at a larger level, another conflict emerges. The very fact that spirituality has been commercialised into a full-fledged industry with luxury retreats, high-end products and apps – is at odds with the concepts of spirituality itself.

The spiritual practices that gave people refuge when they were disillusioned with Western consumerism have ironically been packaged in the same consumerist ways, making it seem like spiritual achievement is available only to those with the right amount of money.

Ultimately, there is a lot that the West can absorb from Eastern culture. The multi-directional flow of ideas and knowledge is crucial in today’s world, but not at the cost of our cultural practices being flattened out, commercialised and oversimplified into something they are not.

[Chakra Healing painting by Julia Watkins , others from different sources]

Mahabahu.com is an Online Magazine with collection of premium Assamese and English articles and posts with cultural base and modern thinking. You can send your articles to editor@mahabahu.com / editor@mahabahoo.com ( For Assamese article, Unicode font is necessary)