“More distant than the stars and nearer than the eye: the commonness of mystical experience in Sufism and Hindu bhakti-marga”

More distant than the stars and nearer than the eye: the commonness of mystical experience in Sufism and Hindu bhakti-marga

Sanjeev Kumar Nath

The first part of the title—“more distant than stars and nearer than the eye” is a phrase from T S Eliot’s poem Marina which is generally considered to be one of the poems dealing with the poet’s experience of conversion into Anglo-Catholicism.

Eliot used the phrase “more distant than stars and nearer than the eye” to gesture towards a mystery involving a deeply felt religious or mystical experience. It is extraordinarily different, distant from all other experiences, and yet at the same time it has the sense of being an essentially intimate experience of the self.

Additionally, the Christian connotations of Eliot’s phrase add yet another dimension to the issue at hand: the commonality of mystical experience in Sufism and Hindu devotional practice.

Also, there are people who would have us believe that Islam and Hinduism are so radically different from one another, so distant from one another that there could be no point of contact.

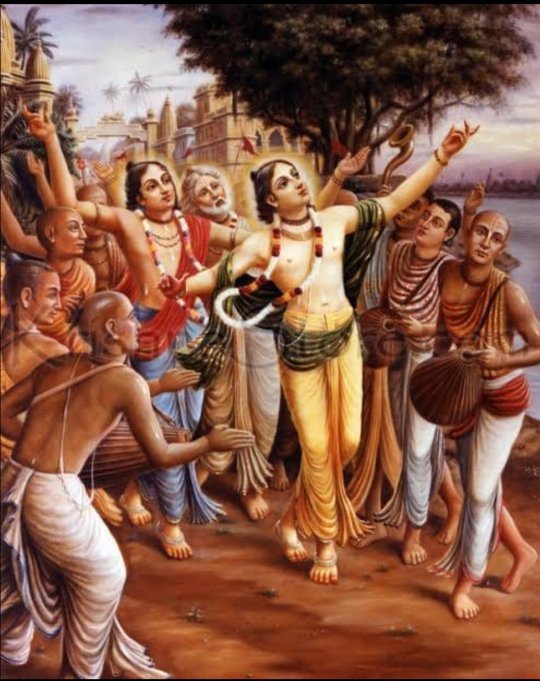

In this paper my attempt is to emphasize the commonality between the Islamic mystical tradition of Sufism and Hindu devotional practice exemplified by mystics such as Ramakrishna Paramhamsa whose journey towards Truth is through the practice of intense devotion for God.

There is of course, divergence of scholarly opinion on the question of Sufism’s relationship with Islam: whether it is integral to Islamic tradition or whether it is at the periphery or even outside Islamic practice. I think such questions arise because of the clearly mystical dimension of Sufism, but can anyone deny something that is at the source of the entire Islamic tradition—the Prophet’s mystical communication with divinity?

Prophet Muhammad’s repeated communication with the archangel Gabriel is essentially a wonderful mystical experience, perhaps the biggest and the most marvellous mystical occurrence of all times as far as Muslims are concerned. Of course, mystical experiences are deeply personal experiences and resist all kinds of attempts at institutional or rational explanation.

When we talk of the commonalities among mystical experiences of the Sufis and those of mystics from the Hindu bhakti-marga tradition, we must, however, remember that even as we look at the commonalities we must not forget the distinctive and divergent qualities of each tradition. After all, Sufi thought is essentially rooted in Islamic ideas and the Holy Quran just as Hindu devotion is connected to some of the ideas of the Hindu scriptures.

There is a special need of understanding and appreciating this idea—the idea of the uniqueness of each tradition even as we talk of their common ground—because nowadays there are too many so called New Age gurus who are out to dilute the richness and the variety that the world’s religions have to offer. They tend to make a hotchpotch of all religions and sell that off as a modern or postmodern spiritual tonic.

Today, ultra-modern experts on religion and spirituality are trying to sell religion in the shopping malls. Health clubs and wellness institutes in the West teach what they describe as Sufi dancing.

“New Age spiritual gurus sell package deals offering Zen without Buddhism, Vedanta without Hinduism—and now we have a Sufism without Islam.” (Dehlvi, 22) One mustn’t forget that Sufism developed from within Islamic traditions, and that although Sufism, like other mystic traditions, “offers universal ethics and meditation practices, its internal spiritual current cannot be alienated from its outward Islamic dimensions.” (Dehlvi, 22).

Thus, even as we look at the commonalities among the mystical practices involving Sufism and Hindu bhakti-marga, we must understand the essentially Islamic character of Sufism.

Perhaps the commonalities exist because mystical experiences in all religious traditions share many common features. What William James said about mystical experience more than a hundred years ago still holds good. He said all mystical experience is characterized by ineffability, noetic quality, transiency, and passivity.

For James a mystical state of consciousness is ineffable in the sense that it defies expression; the mystic cannot adequately communicate his or her experience to others. A mystical experience is noetic in character because it provides knowledge, often knowledge which cannot be attained by the discursive intellect. Mystical experiences are transient, lasting only a few moments or for a brief period of time.

James also says that these experiences are passive states, with the mystics reporting that such experiences seem to be imposed on them. Of course, many mystics, including Sufis, prepare themselves in various ways for entering into these special states of consciousness, but when the moment comes, it has the effect of occurring on its own and not being dependent on volition.

Ramakrishna Paramhamsa the great Bengali mystic has talked about the difficulty he faced in communicating the nature of his Samadhi, a deep mystical trance. Speaking in the language of parables, Ramakrishna says that a salt doll went to measure the depth of the sea, but could not come back to report its findings. Similarly, he has talked about the transitory character of mystical experiences.

He says that one can have a strikingly deep insight into the reality or the self during the moment of mystical ecstasy, but that insight can suddenly go away: it is like someone separating the thick covering of water lettuce on the surface of a water body and looking in to see a reflection of the face. The moment one takes one’s hands away from the water lettuce, the thick green covering closes as before, and the reflection is lost.

Mystical experiences are not understood easily, but they never fail to fascinate people. It is true that “Mysticism is one of the least understood aspects of spiritual experience. It is, in a sense, hidden from the regular religious practitioner—a sometimes mysterious and strange aspect of the religious life.

Nevertheless, it has never failed to attract people through the centuries” (Oliver 3). In all religious traditions, mystics aspire for immediate and intimate contact with God and do not seem to lay much stress on following the mainstream orthodox tradition with all the official rites and rituals. Many great Hindu devotees including Ramakrishna insist that one must attain true discretion by never forgetting that the world is not real and that God alone is real.

Sufism also lays great emphasis on remembrance, and what needs to be remembered is “the reality, the real (haqq), which is nothing but the plain fact of God’s activity and presence in the world and the soul.” (Chittick 63)

The experience of connectedness with God that Sufism and other mystical traditions share is something that is valuable and reassuring for many people. Despite the spread of a global, urban culture based on technology, trade, consumerism and careerism, many people feel incomplete or even empty without realizing the spiritual dimension of their selves.

Also, “For many of us, the idea that we are part of something greater, which is also a part of us in return, is a reassuring idea. It provides a sense of purpose and significance in life. Such a mystical idea has been with us for a long time in various forms and in various traditions. Yet there is a timelessness about such ideas. They appeal to human beings in all ages, including our computer-based, globalized society.” (Oliver 3)

It is perhaps in this context that we may understand why, for instance, the poetry of the Sufi saint Jalaluddin Rumi (1207-1273) is so popular in the west today. Sufi saints have never stopped with the attainment of their personal contact with the Divine, but have always made use of their esoteric experience by reaching out to the people, teaching them how to enrich their spiritual lives, how to be good Muslims, good human beings.

Rumi, for instance, wrote poetry in order to transform his listeners and readers, to take them out of themselves, to make them drunk with the Divine.

In this disenchanted contemporary age, rootless human beings float aimlessly in a sort of postmodern illusoriness, and what Rumi has to offer has significance for all of us. His poetry ignites a yearning for attaining greater levels of awareness in ourselves, for connecting with something unimaginably greater than ourselves, a life-enhancing whole.

The Western Christian concept of mystical union or unio mystica, the moksha or “salvation” of Hinduism, the state of bliss or nirvana in Buddhism and “the snuffing out of self” or fana in Islam are actually allied experiences. We can also see this as the result of the bonding that takes place between the individual soul and God.

In her book The Essentials of Mysticism and Other Essays Evelyn Underhill considers the criticism that mystics have to face regarding the allegedly closed, individual nature of their experiences. If a mystical experience cannot be represented in ordinary language, what use does it have save perhaps for some personal satisfaction to the mystic herself?

Underhill argues that the great mystic is not a spiritual individualist cut off from the rest of the world, but a representative of the age:The great mystic’s loneliness is a consecrated loneliness. When he ascends to that encounter with Divine Reality which is his peculiar privilege, he is not a spiritual individualist.

He goes as the ambassador of the race. His spirit is not, so to speak, a “spark flying upwards” from this into that world, flung out from the mass of humanity, cut off; a little, separate, brilliant thing. It is more like a feeler, a tentacle, which life as a whole stretches out into that supersensual world which envelops him. (Underhill, 42)

Underhill further asserts that after his union with Divine Reality, the true mystic reaches out to his fellow beings, passing on to them the revelation that he has received, becoming something like a mediator between the transcendent and his fellow human beings. Thus, it is wrong to argue that mystics are aloof from the realities of the world and are cocooned in their own esoteric, personal experiences.

An overwhelming consciousness of God and of one’s own soul constitutes one of the important features of any mystical experience including Sufi experience. According to Palmer,

“The Sufis consider it an axiom that the world must have had a Creator. They affirm that He is One, Ancient, First and Last, the End and Limit of all things, Incomparable, Unchangeable, Indivisible, and Immaterial, not subject to the laws of time, place, or direction; possessing the attributes of holiness, and exempt from all opposite qualities.” (Palmer, 22)

Sufis are known for their scrupulous observance of divine law as stated in the Quran and the traditional sayings of the Prophet. Throughout the ages, Sufis have also been actively educating the masses and deepening the spiritual lives of Muslims.

One of the evidences of the commonality of the mystics’ way is to observe the similar manner in which mystics from Christian, Sufi and other traditions talk about the degrees of spiritual ascent. They talk about many stages through which the soul rises to the highest level of truth.

Thus, the Christian saint St. Teresa talks of seven steps of spiritual ascension just as the Sufi mystics talk of seven stages of the soul’s ascent to God. It is quite obvious that the landmarks described may be different for different traditions, but the road is the same.

That Sufism is not errant Islam but the very core of Islam is evident from the fact that the central personality of Islam, Prophet Muhammad, is not just the central figure in Sufism, but also the axis around which the Sufi world revolves. In fact, Prophet Muhammad is the most perfect of all mystics, in constant contact with God, even in deep sleep, and the Sufi’s endeavour is to venerate the Prophet and follow Him.

For a Sufi, to love and adore the Prophet—who is Habib Allah, i.e., ‘beloved of God’—is to love and adore God. All this is in keeping with the teaching of the Holy Quran which establishes the Prophet’s superiority over all earlier prophets, and warns against referring to or dealing with the Prophet except in the most respectful manner. Sufis believe that Allah the merciful can forgive anything except disrespect or disregard for his beloved Muhammad.

The Bhkati movement of medieval India was fuelled by Islam in different ways. Some sections of Hindus, particularly those on the lower rungs of the caste hierarchy, felt attracted towards Islam which did not recognize caste hierarchy and the special privileges of the priestly class. This propelled Hindu leaders to think about ways of saving their religion from extinction, and they found the method of Bhakti to suit their needs perfectly.

Many of the Bhakti reformers preached the unity of God, as in Islam, and also the oneness of humanity. Bhakti reformers like Kabir and Guru Nanak Dev were greatly influenced by the teachings of Sufi saints who taught that the human soul could unite with God through sincere devotion and love for God and for fellow human beings, and that only a true teacher or guru could guide an individual on the path of God realization.

Sufism and Bhakti Marga are parallel in their emphasis on the need of the individual soul’s union with God through intense devotion and their disregard for mere conventional rituals.

Sufism, which spread quickly throughout the Muslim world after its appearance in the 7th century, i.e., the first century of Islam, also reached India at an early date, and interacting with the thought of Indian religious traditions, acquired a new identity in the Indian subcontinent. If we compare the important teachings of the Sufism with those of Bhakti Marga, their many intersections, overlappings and parallelisms become abundantly clear.

Bhakti reformers taught that God was one, although different people might call Him by different names. They taught the importance of good deeds comprising such things as practising honesty, purity and justice in one’s thought and action and abstaining from greed, dishonesty, selfishness, etc. They emphasized the unity of all human beings and sought to abolish caste hierarchies.

Their worship usually consisted of greatly emotional prayers, the repeating of God’s names and singing His glories. Bhakti Marga generally emphasized the importance of the guru or the spiritual preceptor and belittled the importance of rituals. Many of the Bhakti reformers condemned the worship of idols and stressed the need for realizing God in one’s heart or soul.

Sufi saints taught that the highest good that a human being could achieve was to have direct communion with God, i.e., the union of the human soul with God. For Sufis there is only one God, Allah who is omnipotent. In their desire to achieve union with God Sufis generally renounce the ordinary material pleasures of the world and embrace an ascetic way of life.

Sufis emphasized on non-violence and pacificsm so much so that some of the Sufi saints actually became vegetarians and some Hindus may have been attracted to them because of their vegetarianism. They also taught that all human beings were equal in the eye of God, and artificial differences such as caste hierarchies were meaningless. Sufism stressed the importance of the murshid or the spiritual guide who could show the way to a disciple.

Sufi saints insisted on moral practices such as speaking the truth, practising purity, justice, goodness, not stealing, not hurting anyone in any way, and shunning hypocrisy. It is easy to see how the set of values cherished by the two parties are in fact common values.

Another Indian religion, Sikhism, is a religion which has been influenced by Sufism to a significant extent. In his book A History of the Sikhs. (Princeton, N. J. and London, 1963. P 17) Khuswant Singh has famously asserted that “Sikhism was born out of wedlock between Hindusim and Islam” but there are other scholars who have sometimes questioned the correctness of Singh’s statement.

W H McLeod, for instance, has said that Sikhism derives more from the Hindu sant tradition than from Islam. However, no one can deny that Sikh thought is significantly influenced by Islamic, particularly Sufi thought and practice.

Finally, a disclaimer: Discussions such as the present one, are usually dependent on information derived from books, but the great mystics of all traditions—Christian, Muslim, Hindu—have often asserted that the knowledge derived from books is inadequate to the actual realization of truth. Understanding mystical experience is ultimately dependent on mystical experience itself!

Works Cited

Abdulla, Raficq (Transl). Rumi: Words of Paradise. London: Frances Lincoln Ltd., 2000

Chittick, C. William. Sufism: A Beginner’s Guide. Oxford: Oneworld Publications, 2008

Dehlvi, Sadia. Sufism: the Heart of Islam. New Delhi: Harper Collins Publishers India, 2009.

Oliver, Paul. Mysticism: A Guide for the Perplexed. London, NY, etc: Continuum International Publishing Group, 2009.

Palmer, E. H. Oriental Mysticism: a Treatise on the Sufistic and Unitarian Theosophy of the Persians. 2nd Edition. London: Luzac and Co., 1938.

Underhill, Evelyn. The Essentials of Mysticism and Other Essays. Grand Rapids, MI: Christian Classics Ethereal Library. Web. 25 December, 2012. First print edition 1920.

Images from different sources

Mahabahu.com is an Online Magazine with collection of premium Assamese and English articles and posts with cultural base and modern thinking. You can send your articles to editor@mahabahu.com / editor@mahabahoo.com (For Assamese article, Unicode font is necessary)